... why is that the same fucking people derail this thread into god knows where...

Let's try to consolidate and simplify the discussion as it is:

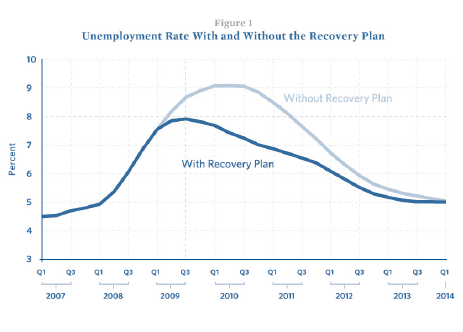

Me: Monetary policy is useless at the momment, since we're already at or near 0%. The Fed can't lower the interest rate to -1%. Therefore Fiscal Policy is the only viable option in order to fight the recession.

I believe that fighting the recession, counter-cyclical policy, is good. Ignoring the moral aspects, it's economically bad to allow deflation to occur (1). Nobody will loan any money, if they can simply gain more value by hoarding it. Nobody will buy anything, if goods will become cheaper. Ignoring the impact a great recession will have on future employment via education and depressed workers, we will have a reduction in long term output. Long term recovery, won't be just an shift in expectation, reduciton in price levels and wages, but a reduction in actual potential output.

(1) I believe deflation will occur, because I believe we are suffering from a demand shock. People are not spending as much as their income as they used to. The aggregate price will go down. Disinflation has been happening, we had a brief period of tiny deflation, and here is the proof:

| Current Inflation Rate | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Sometimes it’s useful to step back slightly from the current fray and ask what we’ve really learned about macroeconomics over, say, the past year and a half. Here’s how I see it: in early 2009 there was a broad divide between two policy factions. One, of which I was part, declared that we were in a liquidity trap, which meant that some of the usual rules no longer applied: the expansion of the Fed’s balance sheet wouldn’t be inflationary — in fact the danger was a slide toward deflation; the government’s borrowing would not lead to a spike in interest rates. The other side declared that we were in imminent danger of runaway inflation, and that federal borrowing would lead to very high interest rates.

What actually happened?

(The dip and rise in the interest rate represents the rise and fall of oh-god-we’re-all-gonna-die fears).

Now, the guys who got it all wrong are winning the political argument, in large part because the Obama administration went for half-measures, and is now being punished for a weak economy — which people like me predicted would happen.

But never forget that as far as the facts go, the Keynesians won this hands down.

Legal Krugman: Lost Decade Looming?

From Paul Krugman on The New York Times’s Op-Ed Page:

Despite a chorus of voices claiming otherwise, we aren’t Greece. We are, however, looking more and more like Japan.

For the last few months, much commentary on the economy — some of it posing as reporting — has had one central theme: policy makers are doing too much. Governments need to stop spending, we’re told. Greece is held up as a cautionary tale, and every uptick in the interest rate on U.S. government bonds is treated as an indication that markets are turning on America over its deficits. Meanwhile, there are continual warnings that inflation is just around the corner, and that the Fed needs to pull back from its efforts to support the economy and get started on its “exit strategy,” tightening credit by selling off assets and raising interest rates.

And what about near-record unemployment, with long-term unemployment worse than at any time since the 1930s? What about the fact that the employment gains of the last few months, although welcome, have, so far, brought back fewer than 500,000 of the more than 8 million jobs lost in the wake of the financial crisis? Hey, worrying about the unemployed is just so 2009.

But the truth is that policy makers aren’t doing too much; they’re doing too little. Recent data don’t suggest that America is heading for a Greece-style collapse of investor confidence. Instead, they suggest that we may be heading for a Japan-style lost decade, trapped in a prolonged era of high unemployment and slow growth.

Let’s talk first about those interest rates. On several occasions over the last year, we’ve been told, after some modest rise in rates, that the bond vigilantes had arrived, that America had better slash its deficit right away or else. Each time, rates soon slid back down. Most recently, in March, there was much ado about the interest rate on U.S. 10-year bonds, which had risen from 3.6 percent to almost 4 percent. “Debt fears send rates up” was the headline at The Wall Street Journal, although there wasn’t actually any evidence that debt fears were responsible.

Since then, however, rates have retraced that rise and then some. As of Thursday, the 10-year rate was below 3.3 percent. I wish I could say that falling interest rates reflect a surge of optimism about U.S. federal finances. What they actually reflect, however, is a surge of pessimism about the prospects for economic recovery, pessimism that has sent investors fleeing out of anything that looks risky — hence, the plunge in the stock market — into the perceived safety of U.S. government debt.

What’s behind this new pessimism? It partly reflects the troubles in Europe, which have less to do with government debt than you’ve heard; the real problem is that by creating the euro, Europe’s leaders imposed a single currency on economies that weren’t ready for such a move. But there are also warning signs at home, most recently Wednesday’s report on consumer prices, which showed a key measure of inflation falling below 1 percent, bringing it to a 44-year low.

This isn’t really surprising: you expect inflation to fall in the face of mass unemployment and excess capacity. But it is nonetheless really bad news. Low inflation, or worse yet deflation, tends to perpetuate an economic slump, because it encourages people to hoard cash rather than spend, which keeps the economy depressed, which leads to more deflation. That vicious circle isn’t hypothetical: just ask the Japanese, who entered a deflationary trap in the 1990s and, despite occasional episodes of growth, still can’t get out. And it could happen here.

So what we should really be asking right now isn’t whether we’re about to turn into Greece. We should, instead, be asking what we’re doing to avoid turning Japanese. And the answer is, nothing.

It’s not that nobody understands the risk. I strongly suspect that some officials at the Fed see the Japan parallels all too clearly and wish they could do more to support the economy. But in practice it’s all they can do to contain the tightening impulses of their colleagues, who (like central bankers in the 1930s) remain desperately afraid of inflation despite the absence of any evidence of rising prices. I also suspect that Obama administration economists would very much like to see another stimulus plan. But they know that such a plan would have no chance of getting through a Congress that has been spooked by the deficit hawks.

In short, fear of imaginary threats has prevented any effective response to the real danger facing our economy.

Will the worst happen? Not necessarily. Maybe the economic measures already taken will end up doing the trick, jump-starting a self-sustaining recovery. Certainly, that’s what we’re all hoping. But hope is not a plan.

What happens when you shift the yellow line to the left? What happens to output? What happens to price level?

What happens when you shift the blue line left? What can cause a supply shock (hint: an increase in the price of production factors). When did this famously happen, and what did we call it?

My assumptions on what anti-Keynesians are trying to say are:

1) Because Greece, and other countries in Europe are in danger of defaulting, the restof the world must stop borrowing money.

2) Borrowing money reduces investment, because of the crowding out effect.

3) The last two stimulusis didn't work. Keyensians are cheap because they retroactively claim that "government didn't spend enough", which makes me feel like it's a continual upward spiral of spend, spend, spend.

4) We will suffer from inflation, because we're printing money (hence the ocnversation about commodity money???)

5) Unemployment benefits and government spending only causes inefficiency, because people will not look for work when they're given money.

Did I assume correctly?