| mrstickball said: So, Akvod - How much money should of the US spent during the initial stages of the recession. You argue Obama didn't do enough, so I am curious what would be 'enough'. |

It's not just the ammount of money, but WHERE you allocate it. I'll post the article again, since nobody seems to read anything I post, but just talk pseudo-economics >.<

Summary: Poor people spend a greater percentage of money. Give 10 bucks to a poorer person, and they'll probably buy candy, drinks, etc. Give 10 bucks to a rich person, they'll put it in their wallet, maybe spend 1 dollar on a bottle of water, but save the rest.

Krugman: Stimulus gone bad By Paul Krugman Published: Friday, January 25, 2008 <script type="text/javascript">//

PRINCETON, New Jersey — The White House and House Democrats have reached an agreement on an economic stimulus plan. Unfortunately, the plan - which essentially consists of nothing but tax cuts and gives most of those tax cuts to people in fairly good financial shape - looks like a lemon.

Specifically, the Democrats appear to have buckled in the face of the Bush administration's ideological rigidity, dropping demands for provisions that would have helped those most in need. And those happen to be the same provisions that might actually have made the stimulus plan effective.

Those are harsh words, so let me explain what's going on.

Aside from business tax breaks - which are an unhappy story for another column - the plan gives each worker making less than $75,000 a $300 check, plus additional amounts to people who make enough to pay substantial sums in income tax. This ensures that the bulk of the money would go to people who are doing O.K. financially - which misses the whole point.

The goal of a stimulus plan should be to support overall spending, so as to avert or limit the depth of a recession. If the money that the government lays out doesn't get spent - if it just gets added to people's bank accounts or used to pay off debts - the plan will have failed.

And sending checks to people in good financial shape does little or nothing to increase overall spending. People who have good incomes, good credit and secure employment make spending decisions based on their long-term earning power rather than the size of their latest paycheck. Give such people a few hundred extra dollars, and they'll just put it in the bank.

In fact, that appears to be what mainly happened to the tax rebates affluent Americans received during the last recession in 2001.

On the other hand, money delivered to people who aren't in good financial shape - who are short on cash and living check to check - does double duty: It alleviates hardship and also pumps up consumer spending.

That's why many of the stimulus proposals we were hearing just a few days ago focused in the first place on expanding programs that specifically help people who have fallen on hard times, especially unemployment insurance and food stamps. And these were the stimulus ideas that received the highest grades in a recent analysis by the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office.

There was also some talk among Democrats about providing temporary aid to state and local governments, whose finances are being pummeled by the weakening economy. Like help for the unemployed, this would have done double duty, averting hardship and heading off spending cuts that could worsen the downturn.

But the Bush administration has apparently succeeded in killing all of these ideas, in favor of a plan that mainly gives money to those least likely to spend it.

Why would the administration want to do this? It has nothing to do with economic efficacy: No economic theory or evidence I know of says that upper-middle-class families are more likely to spend rebate checks than the poor and unemployed. Instead, what seems to be happening is that the Bush administration refuses to sign on to anything that it can't call a "tax cut."

Behind that refusal, in turn, lies the administration's commitment to slashing tax rates on the affluent while blocking aid for families in trouble - a commitment that requires maintaining the pretense that government spending is always bad. And the result is a plan that not only fails to deliver help where it's most needed, but is likely to fail as an economic measure.

The words of Franklin Delano Roosevelt come to mind: "We have always known that heedless self-interest was bad morals; we know now that it is bad economics."

And the worst of it is that the Democrats, who should have been in a strong position - does this administration have any credibility left on economic policy? - appear to have caved in almost completely.

Yes, they extracted some concessions, increasing rebates for people with low income while reducing giveaways to the affluent. But basically they allowed themselves to be bullied into doing things the Bush administration's way.

And that could turn out to be a very bad thing.

We don't know for sure how deep the coming slump will be, or even whether it will meet the technical definition of a recession. But there's a real chance not just that it will be a major downturn, but that the usual response to recession - interest rate cuts by the Federal Reserve - won't be sufficient to turn the economy around. (For more on this, see my blog at krugman.blogs.nytimes.com.)

And if that happens, we'll deeply regret the fact that the Bush administration insisted on, and Democrats accepted, a so-called stimulus plan that just won't do the job.

Extra article, (2 years later)

What Went Wrong?

The Obama administration is in a difficult spot. It’s now obvious that the stimulus was much too small; yet there’s virtually no chance of getting additional measures out of Congress. The administration has chosen to deal with this by trying to have it both ways — condemning Republicans, rightly, for obstructionism, while at the same time claiming, falsely, that we’re still on the right track.

How did things end up this way? We’ll never know whether the administration could have passed a bigger plan; we do know that it didn’t try.

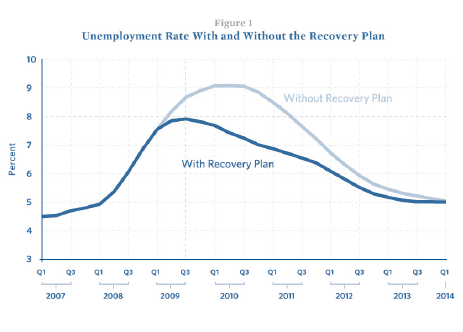

Now, I don’t have any inside information on what really happened; I do talk to WH economists, but they don’t offer — and I don’t ask for — any information on internal wrangling. But based on public reporting, like the Ryan Lizza article on Larry Summers — which reads rather differently now that we know how things are really working out, or more accurately not working out — it looks as if top advisers convinced themselves that even in the absence of stimulus the slump would be nasty, brutish, but not too long. That’s the assumption embedded in the now infamous Romer-Bernstein chart, above. So all policy needed to do was meliorate the worst, while we waited for the economy to recover spontaneously. From the Lizza article:

Summers did not include Romer’s $1.2-trillion projection. The memo argued that the stimulus should not be used to fill the entire output gap; rather, it was “an insurance package against catastrophic failure.”

I don’t know why Summers etc. believed this. Even before the severity of the financial crisis was fully apparent, the recent history of recessions suggested that the jobs picture would continue to worsen long after the recession was technically over. And by the winter of 2008-2009, it was obvious that this was the Big One — which, if the aftermath of previous major crises was any guide, would be followed by multiple years of high unemployment.

Those concerns were what had me fairly frantic in early 2009: I was terribly afraid that the failure of an inadequate stimulus to bring unemployment down would end up being seen as a refutation of the whole idea of stimulus — which is exactly what happened. And by the way, the reason I was for temporary bank nationalization was that it would make it possible to recapitalize banks quickly, and get them lending, which would help make up for the weak stimulus; what happened instead, of course, was gradual recapitalization through profits, with banks not doing much lending along the way.

And here we are. From a strictly economic point of view, we could still fix this: a second big stimulus, plus much more aggressive Fed policy. But politically, we’re stuck: even if the Democrats hold the House in November, they won’t have the votes to do anything major.

I’d like to say something uplifting here; but right now I’m feeling pretty bleak.